The Portrait Artist – Part III

A short story in three parts

This is the final part of my novella length short story. You can find the other parts at the following links:

I watch as he presses the button on the enlarger then agitates the piece of cardboard in his hand as he holds it above the photo paper. Once the exposure is complete he lifts the paper from the tray and moves to the next enlarger pressing the button to expose it to another element of what will soon become the finished print. I’ve seen the process demonstrated before in an educational documentary.

Dropping the photo paper into the developer we watch as the latent image emerges as though by magic. Standing there in this dimly lit room filled with acrid smells, I stare at him openly. It is Isaac standing there before me, leaning over the developer tray, prodding the paper with his gloved hand, peeking nervously at me from the corner of his eye. This man’s flesh and Isaac’s flesh are nearly identical. Only in spirit do they differ. Doppelgänger.

“What sparked your interest in analog photography?” he asks, still looking at the paper floating in its chemical bath.

“I’m not sure. I think it’s the physicality of it. I like the idea of chemical change resulting in a permanent impression.” I still don’t mention anything about Isaac and my desire to build a photographic record.

He lifts the print, moving it to the next tray.

“You said you took photographs of your father when he was ill. Do you still look at them?”

“Sometimes. Not very often really, but I have dusted them off from time to time.”

“Do they help you remember him?”

“Yes and no. Mostly they bring back the time we spent together taking those pictures.”

“What about immediately following his death? You didn’t look at them then?”

“After his death I waited. I didn’t consult the pictures, because I wanted to remember him the way he really was. His presence, the weight of his body. And the mind, the spirit, whatever you want to call it, is a part of that. Who he was, how he carried himself, those things can’t be replicated in a photograph.”

He glances at his watch as it ticks away the seconds before the print will be moved to the final chemical tray.

“There came a time after several years had passed when I would try to recall him, but all I could summon up was this vague, featureless outline. It was then that I started riffling through old photos, but not the figure studies. When I want to remember him I look at old family photographs, snapshots. That’s where I find him. Or at least some recognizable idea of him. And sometimes an old snapshot will bring back a memory of a particular time and place, but other times I wonder if those memories are real or something my mind weaves together to fill in the gaps.”

I thought of the image I’d uncovered of Isaac hidden among the rocks at the crest of the waterfall. It had brought back a recollection of that day, and even the very moment I’d taken the picture. It all felt very real to me. If I thought about it enough I could smell the salty sea breath, feel the sea spray with its sticky droplets clinging to my skin and hair, sense the weight of the camera in my hand as I raised it to compose the image. So many details about that day dwell with remarkable detail in my mind. Were these impressions real or was I just filling in the gaps?

By now the print is swishing round and round the whirlpool of the final wash as we stand entranced by its circular motions. He reaches into the swirling water with a pair of tongs and snatches the print free, then walks across the room to hang it from the drying line using a clothes pin. I follow, standing for a moment staring at the image we have made. It is an experiment in which Isaac’s pale body appears to hover suspended above dark rippling water. Hanging on the line next to it is the original image of the water alone, and in line behind that, the original of Isaac laid out on a table in my garage studio. All possess the same clarity and detail. Who is to say which is true.

“Are you happy with the results?”

I hover for a moment longer, my head poking between the dangling prints.

“Yes, I think so.”

“It’s a bit of magic isn’t it?”

“I can’t even tell the difference between the originals and the one we constructed.”

“I suppose that’s the trouble.”

“The trouble?”

“The trouble with photographs. They seem to tell the truth even when they lie.”

Falling into silence we clean up, returning items to their right place, wiping down counters, shutting off equipment. I gather my binder full of negatives and make an appointment to return and collect my prints which will take some time to dry. As I turn to leave, almost as an afterthought, I ask him if he’d be willing to allow me to photograph him for my project. He says yes.

#

Ever since I was a girl I’ve struggled with the permanence of events. Once something is done it cannot be undone. There is no going back, no do-over, no chance to right a world thrown out of balance by a single event. When I was six years old a neighbor boy I’d befriended shot his brother with his father’s gun. He wasn’t a bad child. He just made a mistake. He didn’t yet understand that permanence. A moment of what felt like play turned into a lifetime of misery. From this point there was no going back. The only chance for redemption was to accept that his brother was gone forever and he was to blame.

Maybe it seems like this incident is different from the moment one finds out they have an incurable disease, but it’s not. Either way there is a point which is now past to which one can never return. The trigger has been pulled, the bullet lodged in the flesh, nothing can take it back, no matter how desperately you may want to. Perhaps Isaac’s disease was always present, a ticking time bomb waiting to go off, an accident waiting to happen, just like the loaded gun sitting in the drawer of the boy’s father’s office.

I remember wishing I had a time machine so we could go back and stop his past self from pulling the trigger. In my child’s mind this seemed plausible. It happened in the movies, why couldn’t it happen in real life?

If you can control the past, then you can control the future. We’re always trying to outrun our past because it’s the only real evidence we have of who we are. Whatever we want for ourselves, whatever we want to be or believe about ourselves, the past is the only indicator of truth, the only unit by which we can measure how well we know ourselves in the present. But the past is also a fable, a story we tell ourselves, and we can choose how to tell it. As I piece together images of Isaac with those of a healthy, able-bodied man I wonder if altering the record of the past can somehow alter the future.

I keep coming back to the photograph of Isaac’s twisted foot. That’s really where this all began. He started walking through the bottoms of his shoes. I remember the first time it happened. He’d bought an expensive new pair of dress shoes for work and in only a couple months he’d worn a hole clean through the bottom of the left shoe. At the time we blamed it on the quality of the shoes, appalled at how such an expensive item could be so poorly made. But then it happened again and again with pair after pair. Before long he was wearing holes in his socks too. A pair of socks wouldn’t last him a month before he’d worn a hole in the bottom. Then there was the tightness in his big toe. The toe would pull inward, jamming itself up against the other toes. The tightness had become uncomfortable and he’d bought a mechanical device with a crank which allowed him to adjust the position of the big toe to alleviate tension. Turning the little crank his big toe began to pull away from the other toes like a medieval drawbridge rising over a moat.

His left foot and then his left hand. He had always been an expert typist until one day his left hand became clumsy and slow. He’d be typing just the way he always had, but the hand wouldn’t operate. There was nothing wrong with the hand, at least nothing that could be pinpointed. There was no arthritis, he didn’t have carpal tunnel. But the signals from the brain telling the hand to move had somehow become blocked. The communication had gone fubar, the hand no longer capable of sending nor receiving transmissions.

These were the first signs, which eventually led to our increasing concern, and finally to a series of doctors and a diagnosis. That diagnosis handed down like a sentence from the high court of medical science.

I keep Isaac’s crumpled foot at my side. It serves as a reminder of the unalterable past, even as I seek to alter it. Using the techniques I learned at the lab, I’ve fused Isaac and his doppelgänger seamlessly, rendering Isaac’s disease ravaged body whole again in photographic form. I search my images of Isaac for those of the offending hand and foot and I replace them with the healthy body parts of the man from the lab. I’m building a life size collage, a photographic sculpture if you will. I take the two dimensional images and I bend, twist, and even crumple them in an attempt to lend depth, to mold them into reality. The sculpture looms above my work space, staring down at me as I shuffle through the myriad prints spread out before me, searching for the next piece in my puzzle.

I’ve even begun going back further, to long before there was any inkling of what was to come. Finding old family albums and forgotten envelopes filled with images from a past so distant as to feel like alien transmissions from another world. Family vacations and graduations and birthday parties. Faded historical landmarks looming above sunblasted figures wearing perfunctory smiles, tasseled hats adorning the heads of grinning youths filled with a fearful pride, suburban lawns strewn with the faded relics of a bygone era. In them I find Isaac and I replace his left foot and his left hand with those of the healthy man.

Of course, Isaac does not know about any of this. I’m not sure what he would think if he did. I’ve banished him from my studio, claiming a need for a space of my own. And he, in his good natured benevolence, has granted it to me without question.

#

I become more and more convinced as each day passes that transforming the flat, lifeless pieces of paper containing my photographic records into the three-dimensional reality of sculpture was the correct course of action. I’ve been researching a bit on the subject of sculpture and it has expanded my understanding of what this work means. A sculpture is not purely imaginary, it is a part of the real world. It has weight and mass, occupying space the way a human body does. It is real by way of its dimensionality and its consumption of space. One could even imagine it as a place in and of itself, a place which can be visited the way one visits a friend or loved one.

And isn’t this precisely my goal? To create an artifact which is more than a flat two dimensional snippet, but a manifestation of the person that is Isaac? A sculpture is something tactile. Reach out your hand and feel its contours, its edges, know where it begins and ends. You can sense its presence in a room, the way you sense the presence of another body. You can almost imagine it coming to life, living and breathing along side you.

Just as I turn the page in the book open before me, the air-conditioning clicks on again and I’m hit with the blast of its icy cold breath. I must be sitting somewhere near a vent, but I cannot seem to locate it, and every time I move to a different location it follows. My arms and legs instantly blossom with tiny lumps of goose flesh and I shift in my seat uncomfortably, glancing up from my reading. Looking out across the library my eyes scan the clusters of heavily lacquered oak tables and chairs flanked by rows of tall metal shelves containing the wisdom of the ages.

On the far side of the room white light pours through a large bank of windows, and it is there, in near silhouette, that my gaze falls upon a familiar face. I do a double take and realize it is Isaac’s face. Only it’s not Isaac, it’s the man from the photo lab. We are far enough apart that he doesn’t notice me. I try to shrink into myself, hoping to remain unseen. He appears to be gathering his things as he scoops up a number of large tomes from the table before him, stacking them awkwardly in his arms then making his way to the circulation desk. I watch as his plunks his load onto the counter and briefly converses with the librarian before taking his leave. The moment he walks out the door I shoot out of my seat zigzagging my way through tables and chairs until I’m standing in precisely the spot he’s just vacated.

Imprinted onto the coated surface of the table is the gradually fading impression of three fingers and a rapidly diminishing palm. The sticky hot mark now a bread loaf shape complete with scoring across the top, now a crescent moon, now a tiny dot, then gone. An empty paper coffee cup with corrugated cardboard sleeve is all that remains of his presence except for a single strand of black hair, his black hair. I pinch it between my thumb and forefinger and raise it into my line of sight. It is exactly like Isaac’s hair, deep black and coarse, fallen from a thick and beautiful mane. Not quite understanding why, I decide to keep it. With my free hand I fish a small piece of paper containing the scribbles of call numbers from my pocket, and folding it in half, I gently place the delicate strand into the crease. Peering at the dark hair as it rests there against the white paper, I fold the sides and top, creating a small pouch for safe keeping of my specimen.

#

I had a strange dream last night. I was searching for treasure. What the treasure was I cannot say, but I understood, or was somehow made to know that I would find it hiding in the light. That’s the exact phrase which was in my head: hiding in the light. It was given to me by some figure I didn’t recognize or cannot recall. I thought I had it figured out. I thought I knew where I would find the treasure. Then just as I emerged into a beautiful and bright day, a solar eclipse rapidly consumed the light and all grew dark and still. The birds stopped singing and the squirrels ceased their rustling in the bushes and the trees, even the beetles and the roaches and all the tiny crawling things seemed to take heed as everything came to a halt. I looked up into the sky at a black sun encircled by only the tiniest sliver of corona, and the world grew darker still. And I knew that the treasure was lost to me now. Only darkness would remain.

I woke remembering and not remembering, feeling a sense of anxiety and something else, something that felt like shrinking, as though my body might collapse in on itself.

Now standing in my studio I stare at the thing I have created which has begun to sprout wiry black hair. The other day when I returned from the library, I plastered the hair I’d collected onto the sculpture. I don’t know why I did it. Somehow it felt like the next step in the process. The hair growth is curious and unexpected, a phenomenon which I can find no reasonable explanation for. I restlessly shuffle through the pile of photographs scattered across my work table and suddenly I am hit by a wave of nausea and the shrinking feeling returns. I desperately need to see Isaac. To touch his skin, to feel the warmth of his body, his presence beside me.

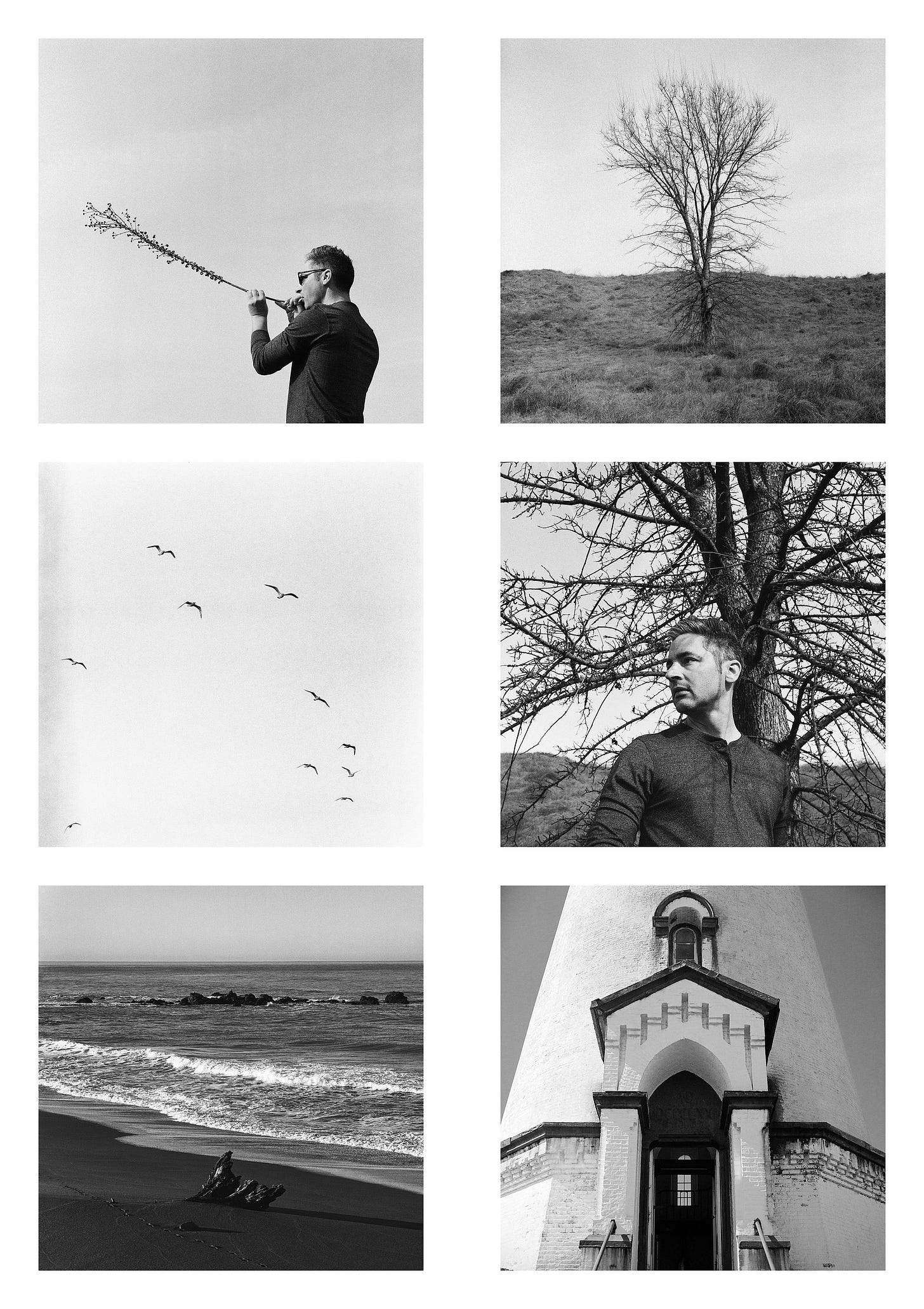

Back inside the house, golden light pours through the western windows and I realize it’s nearing sunset. I’ve spent the entire day in my studio though I managed to accomplish almost nothing. Isaac is nowhere to be found. His collection of pill bottles stand in line on his bedside table like pawns in a game of chess, clothes lie strewn about on the unmade bed. In his office an empty coffee mug rests, hardened brown sludge plastered to its bottom. Making my way out to the kitchen I spy a small white envelope tucked beneath the coffee canister. Inside is a note written on the back of an old 4x6 photograph. The note is brief, scrawled in blue and slightly smudged, the waxy texture of the photo backing serving as a poor medium for the absorption of ink. He’s gone to the support group meeting without me not wanting to disrupt my work. I turn the photograph over. It’s a picture of me and Isaac together, probably five or so years ago now. We’re standing on what looks like a cold and dreary beach blanketed in blue fog. It’s a rare image of the two of us together.

I tuck the photograph into my back pocket, grab my car keys from the basket on the kitchen island, then rush out the door. Perhaps I can still catch him at the meeting.

I race down mostly empty streets to the church. When I arrive outside the church basement, the doors are locked and all is dark as I peer through the windows where I can make out nothing more than vague outlines of familiar shapes. I turn back toward the street, looking up and down its length. Just as I’m about to give up, I see Isaac and what looks like the man from before in the polo and kakis, the meeting coordinator, disappearing behind the back of the building. I rush to catch them. Darting around the rear wall, I find myself standing in the empty parking lot. Interspersed street lamps begin to flicker on as a light breeze rustles a few fallen leaves which skitter over the asphalt in tiny bursts. On the far end of the lot I catch sight of two figures as they mount, and quickly ascend, a cement staircase. I follow, breaking into a trot as I cross to the narrow stairs which lead to the roof of the building. The roof is flat and open, flanked to the north by the church tower rising high toward the heavens. There is no one here, and as I survey the area I see nowhere for anyone to hide. The space is wide open, the staircase I have just climbed serving as the only visible escape route.

I walk slowly toward the brick parapet wall and look down on the sidewalk where I stood only moments ago. The sidewalk is empty, the monotony of perfectly square cement slabs unbroken but for a tree’s roots which have burst through, disrupting the conformity of the quiet suburban walkway. A warm gust of wind rouses me and I look up to witness a final sweltering sliver of radiant orange dipping into obscurity beneath the horizon. The sky begins to glow with a violent warmth, yellow and pink seeping upward from the vanishing point, gradating into softer blue and finally deep purple. I remove the photograph from my back pocket and begin to study it. A whitish haze has begun to consume the left side of the picture where Isaac’s likeness resides and I swipe at it with my thumb.

A series of uneven thuds issues from the stairwell and my confusion quickly shifts to horror as the seething limbs of the ruined man come gradually into view. He trudges toward me over the cracked tar rooftop one foot shooting wildly out in front of him as he drags the other slowly behind. I stand frozen in terror, watching him approach, wondering whether what I’m seeing is real or the grotesque invention of some night terror spilled over into the waking world.

“Are yokay?”

I stand quiet and stare deep into his eyes until they hover disembodied, unprepared to have heard him speak, startled to have been greeted with such an ordinary and human expression of concern.

“Ye…yes. Yes, I’m fine. Sorry, am I not supposed to be up here?”

“Is jstunusal. Is getting layt.” His words come hurried at first, then gradually slowing like a toddler trying to run then remembering as he clamors over his stumbling feet to reign himself in. “I remember you. Ycayme t’th…to the meeting.”

“Yes, I was here with my husband.”

“And where isee now?”

“I…I don’t know.”

“Aryou looking forim?”

“I was, yes.”

“Its hard isnit?”

“What is?”

“Bee-ing with dis-eease.”

The last syllables come slow and long as he almost sounds out that fateful word. Disease. And for the first time I am seeing him. I do not glance quickly away nor do I stare too hard into his eyes. I take him in, moving my gaze over his body, seeing the human form hidden beneath the sea of ticks and tremors and involuntary movements. He sees me seeing him and for a moment, perhaps the first in a long time, there is calm, a lucidity which crawls over my flesh in tiny sparks of energy, compelling me toward I know not what. Though he says nothing more, there is a sense of satisfaction as he turns to leave, making his awkward way back toward the stairs.

I look up into the now darkening sky, wisps of cloud turned steely gray as the last vestiges of light drain below the horizon. I must find my way back to Isaac. That’s all that matters now, the photographs, the sculpture, the doppelgänger from the lab, it’s all a distraction. I’ve wanted desperately to slow down each moment I’ve shared with Isaac, to play them out frame by frame, analyzing each gesture in minute detail, to freeze the fragments of a life into the solid and the everlasting. But as I think on that lifeless pile of photographs now, all I see is stillness and death.

This blessed sense of clarity fades along with the last traces of color from the sky, gone as quickly as it arrived, and I am enveloped once more in impenetrable dark.

Driving back I think again of the photograph in my pocket and wonder what made Isaac write his note on the back of it, where he even found it. It feels as though my past with him is slipping away, enveloped in that cold blue fog. Then I think of the ruined man, his gait, his roiling limbs, his slurred speech.

I shut my eyes against the image of Isaac’s face on his body as it flashes across my mind’s eye. When I open them, the darkened road stretches out into the black night. I speed ahead, training my gaze on the white dashed lane markings as they emerge into the focused beam of my headlights only to fade again into darkness.

#

I woke this morning to a strange call from the man at the lab. He called himself Isaac, “This is Isaac from the lab,” he said. He told me I’d left some prints there to dry and never come to collect them. He just wanted to remind me they were there whenever I was ready to pick them up. Now I find myself racking my brain trying to remember the details of the photo shoot we did together. Shouldn’t I have learned his name then? I rummage through the images from our shoot. I’ve marked them on the back with red Sharpy, just a circular red mark, to indicate which are of the man and which of Isaac. Lining the images of Isaac and those of the man up side by side it is impossible to tell the difference. They are identical in every way. Moles, birthmarks, scars, all the same.

Feeling flustered I begin examining my sculpture. I’ve created a three dimensional collage from my photographic prints matching the height and overall size of Isaac. It is impressive in its detail. The printed images perfectly manipulated to each curve and line of Isaac’s body. It truly has transformed into a sculpture. As I walk around it, viewing it from each side, I am slowly overcome with a sense of revulsion. I can no longer tell which parts belong to Isaac and which to the man. I feel the need to purge myself of the imposter’s presence.

I begin tearing away at the sculpture. The pieces don’t want to come loose so I grab a box cutter and start cutting. I remove layer after layer. Bits and pieces of arms, legs, feet, hands falling to the floor. I cannot avoid the cringe inducing tickle of the strange hairy growth now crawling over the body of the thing. The more I peel away the more desperate I become to destroy this abomination. I slice heavily with my knife slashing deep into the tissue. As I pull the knife away a thin red line appears then quickly fills with a deeper red as what looks like blood oozes out and begins to trickle down the side of the sculpture collecting in a small pool at my feet. I pause staring at the open wound, lightly brushing it with my finger which comes away stained red.

I move to the face, tearing at the pieces more gently now, removing them one by one, piling them on the work table behind me. Peeling away a particularly long piece, something gray and cold, yet soft and supple reveals itself beneath. As I continue to pull away flat strips imprinted with eyes, cheeks, eyebrows, chin, I find Isaac starting up at me, his skin like alabaster. I poke at the soft, decaying flesh in disbelief wondering when I will wake from this nightmare.

It dawns on me that I have not spoken to Isaac in days, don’t even know where he is or what he’s doing. I abandon my task and slip back through the garage door into the house. “Isaac?” I call, but there is no answer. I search the rooms one by one, finding no trace of him. I rummage through the drawer beside his bed expecting to find his collection of prescription bottles, but the drawer is empty. A few balls of lint and a tiny red spider scrambling for escape are all I find. My phone begins to ring from the other room, but I dare not answer. I search the cabinets and the book shelves, even the refrigerator. There is no trace of Isaac anywhere. No books, no photo albums, no favorite foods.

On the kitchen counter I find the photograph from the other day, the one with his note written on the back, only there is nothing scrawled across the white backing which bears only the faint markings of the paper manufacturer’s stamp in repeat. Turning it over I find an image of myself alone on an empty and desolate beach, no Isaac, no anything but fog and wet sand and the slightest hint of waves receding into the background.

Gathering my keys and purse I head for the door, leaving my cell phone behind. Sitting in the running car in the bright light of midday, the flesh of my legs burning against the hot leather seats, I toss the photograph into the backseat, adjust my rearview mirror, and back down the driveway.